Critic

장진 작가의 ‘心心한 風景’

최 승 훈 I 대구미술관 관장

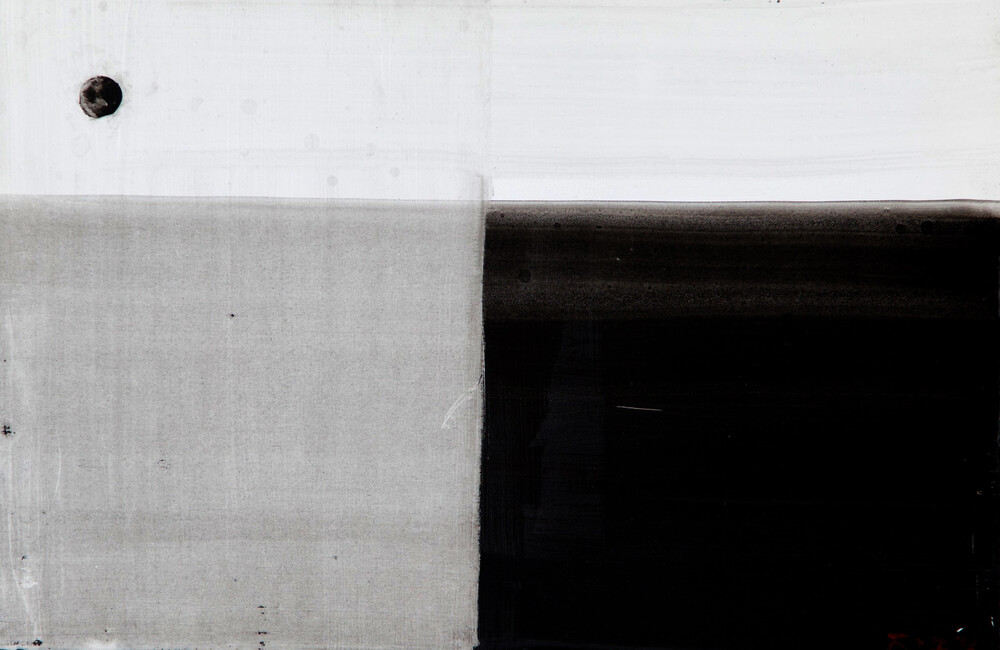

心心한 풍경 (Moonlight prism14) 한지에 먹, 35x23cm, 2016

장진의 작업개념은 달빛의 개념이다. 달은 본래 신화적 상징물로 생성, 탄생, 소멸의 보편적 법칙에 따라 움직이고 순환적 생명을 지닌 천체인 것이다. 그러므로 ‘달빛’은 재생과 부활의 영토로 이끄는 생명의 탯줄이며 구원의 상징물이다. ‘달’이 떠오르는 순간, 지상과 천상은 하나로 연결되고 지상의 삶은 새로운 차원으로 진입하여 빛을 뿜게 되는 것이다.

그의 그림에서 반복되는 소재들-대지, 수면, 수풀, 바람, 구름, 하늘, 달, 천공(天空)-은 서로 교응하고 수렴하면서 동일한 의미 선상에 놓여 있으면서 각각 아름답게 은은한 빛을 분광한다. 그 광휘는 유기적으로 연결되어 시적 감흥을 불러일으키고 신화적 아우라를 형성한다. 그의 그림은 신화적 상상의 지평이 아름답게 펼쳐지는 순간이라고 할 수 있다.

이 신화적 아우라는 대상과의 관조 상태에서 가능해진다. 우선 외형적 접근을 해 보면 연상되는 바는 다양하다. 거친 필선, 동그란 원, 군집의 건물들을 보며 스산한 공기의 흐름 또는 우주의 깊은 공간을 느낄 수도 있다. 그의 작품세계에는 그만큼 다양한 요소들이 존재하고, 넓은 영역에 걸쳐 어느 특정한 형식과 방법에 갇혀있지 않고 자유롭게 진행되고 있다.

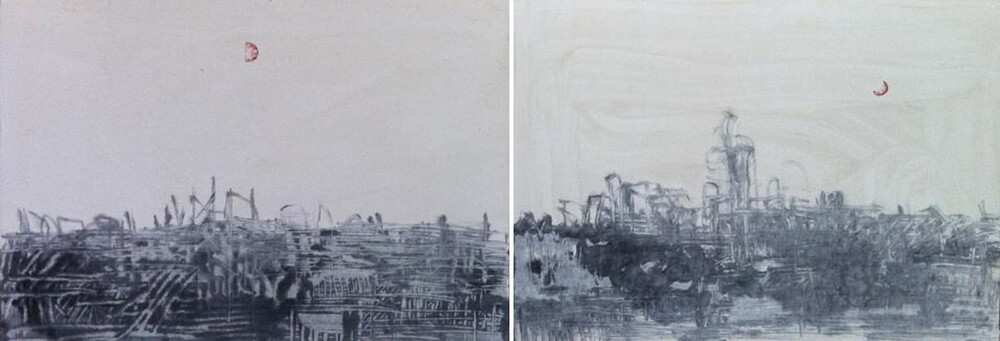

특히 먹색의 부드럽게 스미는 효과는 더욱 몽환적 분위기를 북돋운다. 그림에서 둥글게 나타나는 것은 달의 표상이며 달의 윤곽을 먹의 농담과 필(筆)의 운용에 따라 다양한 표정을 담아 냄으로써 때론 깊은 천공(天空)을 느끼게 하고 때론 강력한 에너지를 뿜어내는 듯한 느낌도 준다. 아주 단아하게 하늘에 떠 있는 달에서 부터 어두움 속에 밝은 빛이 느껴지는 달까지 시시각각 변화하는 달의 다양한 표정들이 살아 있다.

달을 그렸을 때와 마찬가지로 수면을 연상시키는 그림에서도 주도하고 있는 분위기는 명상의 공간이다. 그 속에 보이는 수풀은 목가적 분위기를 진하게 전한다. 구름의 달무리와 풀의 미세한 흔들림이 청량한 공기의 흐름을 감지하게 만든다. 야경을 그린 도심의 표정도 이러한 작가의 의도를 일관성 있게 보여준다. 번잡한 도시의 소음과 일상은 밤의 어두움에 묻히고 빌딩의 집단적 윤곽만이 어슴프레 나타난다. 아늑하게 밤이 내리면 도시는 한순간에 고요한 묵상의 시간에 잠긴다.

화면에 두 개나 등장하는 달은, 사실 비논리적 설정이겠지만, 시각적으로는 전혀 어색하지 않다. 붉은 색의 달은 하늘의 빈 공간에 밀도를 부여하고 있어서 화면 구성에서도 안정적이며 산뜻하기까지 하다. 두 달은 새로운 시각적 언표로써 그의 시(時)와 간(間)의 개념적 측면을 읽을 수 있는 부분이다. 즉 시간의 층위를 생각할 수 있고 기억의 겹침으로 볼 수 있다.

우선 장진의 ‘달빛’ 이 지니는 의미와 뉘앙스는 매우 중요하다. 대낮이 갖는 명료함과 뚜렷한 목적을 전제로하는 일상성 동적 공간과 속도감 등등의 요소들로 대조하여 볼 때, 달빛이 지니는 은은함과 어둠에 묻힌 모호한 정적 공간, 어슴프레함, 신비함은 다분히 명상적인 상태로 이어지고 대도시의 풍경은 달빛 아래에선 목가적인 것으로 나타난다. 작품에서 보이는 명상적 분위기는 반복해서 그어대는 무상적 행위와 하나의 맥을 형성하고 있다. 그의 단순반복적 행위는 인위를 초극하는 정신상태의 화면으로 만든다.

그가 보여주는 달의 관념성은 마치 사군자화가 지니는 추상성과 맥이 닿아 있다. 그의 그림에서 달, 풀, 구름 등등의 대상은 ‘무엇’이라기보다 ‘무엇 같은 것’이라는 식의 접근이 타당할 것이다. 즉 달, 풀, 구름처럼 보이는 것이라는 식의 설명이 된다. 이것은 동양화가 갖는 사유적 특성이기도하며 장진의 추상적 시각이 관념의 대상에서 비롯됨을 뒷받침한다. 이 점을 미술사가 김정락은 “장진은 그가 머무는 곳에, 즉 현존의 현장에서 그리는 대상을 가장 직접적인 방법으로 채취한다. 주로 시각적인 사생에 그치는 사생이 아니라, 몸으로 그것을 느낀다. 그래서인지 구체적이고 재현적인 조형언어에 대해서는 관심을 약간 여민다. 오성의 개념에 기대어 언급한 것처럼, 눈으로만 대상을 관찰하지는 않는다. 그는 온 몸으로 풍경이 주는 감동을 느낀다” 라고 말한바 있다.

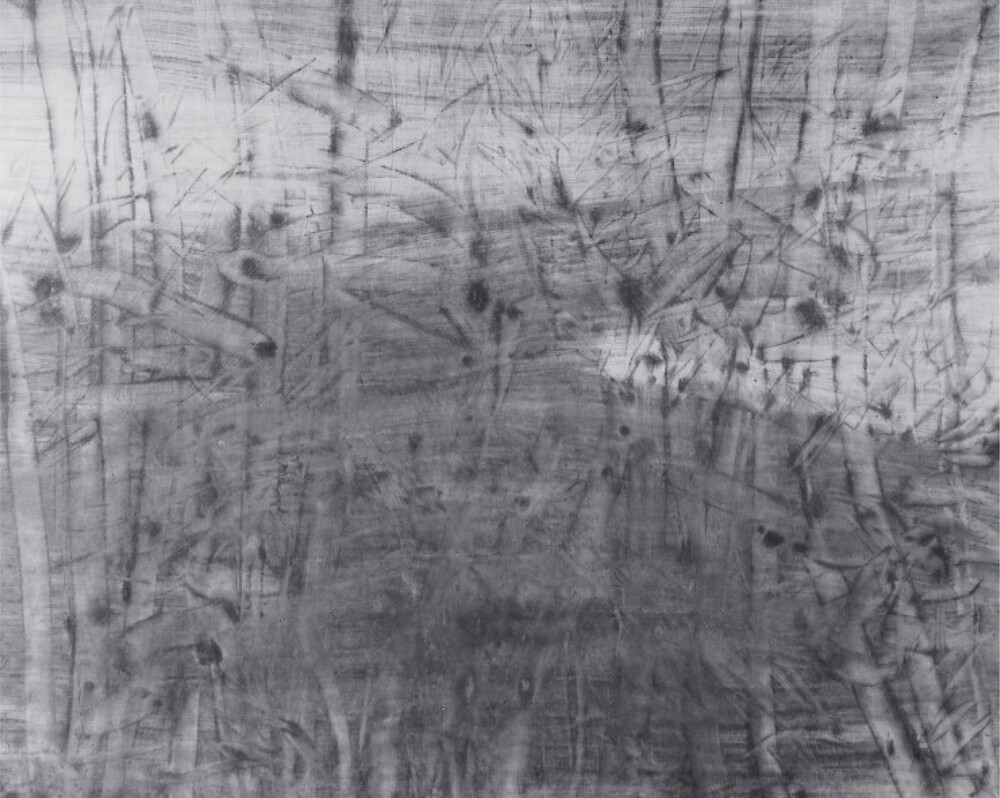

두손으로 마구 문지르고 속필로 그어댄 굵고 가는 선들은 물론 시각적 효과를 위한 의도적 행위이긴 하지만, 그 과정은 다분히 무상적 반복행위로서 장진의 작업관을 명확히 한다. 일반적으로 선(禪)미술로 연결되는 이 무상성은 장진에겐 목가적 풍경, 명상적 분위기, 먹의 카오스적 상태로 나타난다. 그의 그림은 사실성과 사의성, 외연과 내포의 교응하는 관계 위에서 자신 만의 해법을 찾아가는 그의 여정을 여실히 드러내고 있다. 그가 더 많은 길을 통해 더 넓은 영역으로 나아갈 것을 확신한다.

心心한 풍경 (Moonlight prism21) 한지에 먹, 40x55cm, 2016

心心한 풍경 (Moonlight prism17) 한지에 먹, 45x38cm, 2016

기(氣)로 읽어내는 현재와 과거의 풍경들

최근 태초에 기(氣)가 있었다(Im Anfang war die Kraft). _ 요한 볼프강 괴테의 파우스트(Faust) 중에서

김 정 락 I 미술사학

Moonlight prism111(시적공간) 한지에 먹과 채색, 50x50cm, 2016

Moonlight prism112(시적공간) 한지에 먹과 채색, 50x50cm, 2016

詩的空間 1 한지에 먹과 채색, 74x75cm, 2017

詩的空間 6 한지에 먹과 채색, 77x87cm, 2017

詩的空間 9 한지에 먹과 채색, 94x63cm, 2017

Moonlight prism 12(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 104cm, 2008

Moonlight prism 11(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 102cm, 2008

시(詩)적 그리기

은은한 달빛에 젖은 항주 서호에서, 술잔을 들어 취선의 흥을 돋았던 옛 당송 시인들의 시처럼 장진의 동양화는 실로 시적 정서의 응축물이다. 장진의 그림은 시성(詩性)이 어려 있다. 약간은 서정성을 띠지만, 대체로는 서사적인 성격이 지배적이다. 이러한 성격은 하지만 전통적인 수법이나 형식으로 인해 형성된 것은 아니다. 장진은 수묵의 형식을 자기만의 독특한 방법으로 사용한다. 요즘은 모노타입이라는 회화적 판화기법에 수묵화형식을 겹쳐서 그림을 그린다. 붓을 사용하는 듯 하지만, 손으로 직접 드로잉을 수행하거나 우연에 기댄 방식 또한 작업 매뉴얼에 포함되어 있다. 결과는 자유로우면서도 유수 같은 생명력을 재현하는 데에 손색이 없다. 그의 동양화적 방법론은 오히려 서구 모더니즘의 파괴적 형식에 가깝게 보일 수 있다. 20세기 초반부터 추상표현주의까지 줄기차게 반달리즘적인 태도로 형성해 왔던 그리기 행위를 장진은 자신의 것으로 삼는다. 그렇다고 그러한 서구의 폭력적 미학으로 화면을 뒤덮는 것은 아니다. 그의 정서는 그야말로 과거 시인의 흥취를 닮아있다. 적당히 줄여 말하자면, 작가가 동도서기(東道西機)식으로 애매한 절충주의를 추구하거나 그런 식의 해답을 내리고 있다는 것은 아니다.

작가 장진이 동양화가라고 정체성을 규정하는 것은, 그가 속하고 배운 전공의 카테고리 때문은 아니다. 먹이나 적묵을 혹은 석채를 사용하는 동양화 재료에도 있지 않다. 더군다나 그가 마치 남북조시대 사혁(謝赫)이 『고품화록』에서 주창했던 유명한 개념들인 기운생동(氣韻生動)을 적절하게 현대화했다는 의미로서도 아니다. 오히려 작가가 세상을 인지하고 표현하는 과정이 옛 동양화론이 이상적으로 제시했지만, 한 번도 실천하지 못했던 것에 도전하고 있다는 점에서 그렇다. 또한 그는 이 회화의 개념이 가진 의미를 가장 현실적인 방법으로 이끌고, 개념의 철학적 깊이를 유지할 수 있다는 점에서 동양화가라고 칭할 수 있다.

지각의 다른 통로

이성(理性)은 감성(感性)을 때론 무시한다. 따라서 감성으로 얻은 좋은 재료들을 흔히 가치절하하고 자기만의 고유한 관념 혹은 논리의 체계 위에서 떠도는 경우가 많다. 수많은 현대의 작가들, 특히 개념으로 세계와 사물의 관계를 재구성하려는 작가들에게 감성은 단지 작품의 미적 구성을 위한 감미료에 불과하다. 작가 장진에게 감성은 순(純) 재료가 된다. 2009년 금호미술관에서 열렸던 그의 개인전의 제목은 ‘와 닿다’였다. 이성이 사유의 내부로부터 감각의 소여물들을 정리하여 내오는 것과 달리, 작가는 감성에 의지하야 사물과 대상을 만난다. 아니 그것들이 작가에게 능동적으로 다가오며, 그 접근을 작가는 흔쾌하게 받아들인다.

하지만 감성(여기서 말하고자 하는 의미는 영어의 sensation과 유사하다)으로만 그의 작품의 창세기를 설명하기는 힘들다. 필자는 여기서 영악하게 18세기 독일의 관념철학의 한계를 극복하는 인지학적 체제를 빌려오고자 한다. 예컨대 ‘오성(悟性, Verstand)’이란 것이다. 임마누엘 칸트에 의해 정초된 이 개념은 쉽게 풀이하면 가장 순수하고-그러니까 이성의 사유 조작을 거치지 않고-직접적이며(Ding an sich), 거의 신적인 차원의 인식이라고 하겠다. 즉, 깨달음이다. 그래서 이 개념은 이성과 감성 따위로 구성되는 인식구조 안에서 가장 상위의 개념이라고 할 수 있다. 장진의 ‘와 닿다’는 어쩌면 이러한 오성의 지평에서 작가와 대상 그리고 작품과 감상자의 관계를 설정한 것이라고 볼 수 있겠다.

오성을 매개로 하는 인식과정에서 장진은 감각의 부분을 보다 더 강조하며, 이것에 상응하여 시각과 촉각의 공감각을 아우를 수 있는 조형적 구조를 만들어낸다. 이러한 감각성은 인식, 기억, 논리와 같은 사유의 과정에 선행하는 것으로, 작가는 자신이 그 과정에 개입하기 보다는 이 원초적 감각을 그대로 전이하면서 관객이 이후 과정을 수행하도록 돕는 방식을 취한다. 물론 이러한 개념으로 작업을 수행하는 작가가 없는 것은 아니지만, 장진은 최대한 관객의 몫을 남겨주는 부류에 속한다.

기(氣)로 읽는 풍경

장진의 그림이 풍경을 연상시키는 것은 그가 살아온 그리고 기억하는 풍경을 재현하기 때문이며, 오히려 그가 목표하는 바가 그렇다. 그러나 그의 풍경은 사실적이거나-그래서 실경이나 진경 따위의 의미를 지니지 않는다-구체적인 지시성을 지니지 않는다. 그의 풍경은 대상을 윤각으로 포착하는 것이 아니다. 이런 종류의 시각은 이미 세잔 이후에 변질되어 버렸다. 그렇다고 현대의 추상성이 강한 동양화가 변죽을 울리는 심상(心想)적 풍경은 더더욱 아니다. 그의 회화는 가장 본질적이며 원초적인 몸을 매개로 형성하는, 그래서 초 관념적이면서도 가장 현실적인 그리기의 결과물이라고 하겠다. 기(氣)가 전해준 풍경의 본성을 회화라는 방법으로 해독하는 것이 장진의 작업이 지닌 본성이라고 할 수 있다. 작가 장진이 이 반열에 완숙하게 이르렀다는 의미는 아니다. 하지만 적어도 그는 작업이란 수련 활동을 통하여 이 지경에 접근하고 있다는 것은 분명하다. 불교에서 말하는 정진(精進)과 비슷해 보인다.

장진은 그가 머무는 곳에, 즉 현존의 현장에서 그리는 대상을 가장 직접적인 방법으로 채취한다. 주로 시각적인 정보에 그치는 사생이 아니라, 몸으로 그것을 느낀다. 그래서인지 구체적이고 재현적인 조형언어에 대해서는 관심을 약간 여민다. 오성의 개념에 기대어 언급한 것처럼, 장진은 눈으로만 대상을 관찰하지는 않는다. 그는 온 몸으로 풍경이 주는 감동을 느낀다. 한때 유행했던 팝송인 ‘Dancing in the moonlight’가 들려주는 내용처럼, 감수성에 들뜬 작가는 풍경에 춤을 춘다. 다시 말해, 스스로 감성의 스펀지가 된다. 좋게 말해서, 그 자신이 감수체가 되어 자기를 에워싼 환경의 - 이것이 나중에 풍경과 역사라는 장르로 방전한다 - 미묘한 선율을 감지한다. 그 감수체(=작가의 몸)는 작업실 안에서 그것을 풀어놓는다. 온갖 다양하고 별의별 양태의 기운을 행위로서 내뱉는다. 이 지점에서 작가는 잭슨 폴록 같은 추상표현주의 작가들의 행태를 닮았다. 폴록의 작업방식인 뿌리기(dripping act)는 행위에 집중하며, 무의식으로부터 해방된 충동을 캔버스 위에 표출하는 것이지만, 행위의 흔적으로서의 예술성은 과거 아메리카 인디언들의 제의적 행위나 다다 이후 자동기술법(automatism)에 의존하고 있다. 더 나아가 추상표현의 즉흥적이고 직접적인 행위성은 선(禪)사상에서도 기인하였다. 폴록은 그런 의식에 도취하여 그만의 액션페인팅을 완성했던 것이다. 장진에게도 유사한 그리기 행위를 찾을 수 있다. 그러나 폴록이 액션을 자신의 충동에 연관시킨 것에 비해, 장진은 그 원인을 자연이 뿜어내는 기에서 찾는다. 그리고 그의 행위적 그리기는 충동적이기보다는 천성적(transzendental)이다.

장진은 회화를 행위의 흔적으로만 남기는 것을 지양한다. 그가 남긴 화면의 자국들은 행위에 의한 것이지만, 그것이 지향하는 바는 기운에 의해 조성된 새로운 형태의 풍경이다. 즉 형상들이 기화된 풍경화라고 할 수 있다. 즉 순수한 기 상태로 화면에 정착된 풍경이다. 그리고 이 형상들은 시각적 현상도 어느 정도 지니고 있어서 기의 떨림이나 운동을 일으킨 주체들을 인식하게도 해 준다. 흐릿하고 아스라하지만 관객은 그 속에서 모든 움직임, 즉 기를 생성했던 물, 빛, 바람, 소리, 풀 등과 같은 것을 여전히 인식할 수 있다. 만약 그것이 상당부분 추상화되어 있다 해도, 보는 사람에 따라 얼마든지 그 연상을 자극할 수 있는 상태를 장진의 그림은 유지한다.

풍경에서 역사로

자연을 비롯한 환경을 그렸던 대상은 이제 시간으로 옮겨가는 듯하다. 최근에 장진은 자신이 살고 있는 인천의 역사를 그려내고 있다. 간혹 들려보는 인천은 필자에게도 별다른 소회를 남진다. 토박이들은 ‘인천엔 토박이가 없다’고 한다. 과거 제물포라는 작은 어촌이 개항의 중심지가 되었으며, 이윽고 일본제국의 수탈을 도모하기 위한 근대도시로 발전하였고, 인천상륙작전과 같은 역사적 현장으로서 주로 기억된다. 아직도 남아있는 식민지시대의 건물들이 과거의 흔적으로 남아 현재의 개발의지와 소비욕망과 겹쳐진 곳이 인천이다. 그나마도 신도시개발과 같은 잔혹한 자본의 이해 속에서 처연한 역사가 되어가고 있다. 그 가운데에 자리를 튼 레지던시 한 켠에서 장진은-그는 인천사람이다-그 역사를 그려내려고 한다. 그가 역사를 읽는 방법 또한 풍경을 해석하는 방법과 유사하다. 오히려 흔적으로만 남은 역사의 가시적 부분에서 시촉(視觸)을 곤두세우는 태도를 보여준다. 그래서 역사를 아카이브나 인덱스로 나열, 정리하는 대신에 자신의 역사적 감성을 예의 기운으로 환원하여 형상화한다.

장진의 그림이 현재형으로 인식될 수 있는 것은 감정과 몰아에 해당하는 이입이 적어도 싸구려 감상주의에 빠져있지 않다는 것이며, 또 다른 이유는 그의 작법이 스스로와 보는 관객들이 오래 전에 덮어둔 감정의 상처를 다시 까내는 화술이기 때문이다. 즉 현재형이란 의미는 과거와의 끊임없는 동기화에 의해 형성되고 있다는 것을 의미하며, 적어도 장진의 그림에서 그것은 명시적이다. 동기화는 역사를 텍스트가 아닌 그림에 남은 기운의 흔적으로 의미화 하는 것에서 쉽게 찾을 수 있다.

Landscapes of the Past and the Present Drawn with Energy

In the Beginning was the Energy (Im Anfang war die Kraft).

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust -

KIM Jung-rak I Art historian

Moonlight prism111(시적공간) 한지에 먹과 채색, 50x50cm, 2016

詩的空間 6 한지에 먹과 채색, 77x87cm, 2017

詩的空間 5 한지에 먹과 채색, 94x62cm, 2017

Moonlight prism 12(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 104cm, 2008

Moonlight prism 3(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 64cm, 2008

Moonlight prism 6(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 64cm, 2008

Moonlight prism 4(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 64cm, 2008

Poetic Painting

Like the poems by poets of Tang-Song Dynasties who wrote their poems while having a drink in West Lake Hangzhou in the moonlight, Jang Jin’s paintings are a collection of poetic sentiment.

Jang Jin’s paintings are poetic; a little bit lyric, but overall they are epic. This style of painting does not come from traditional ways and forms of Dongyangwha or Eastern painting. Jang Jin takes a unique approach to wash drawing on his own; he incorporates wash drawing techniques into printed paintings called monotypes. It looks like brush painting but he actually drew/painted with hand or relied on a coincidence to happen to complete his works. As a result, the touch is so free and unconstrained, which is suited to express vitality like flowing water. His painting techniques resemble the destructive form of modern Western art; he adopted the vandalistic attitude in art in the early 20th century, which lasted till the era of Abstract Expressionism. But that does not mean his canvas is overwhelmed by the aesthetics of violence in Western culture. His interest and sentiment is quite similar to of poets in the past. Nevertheless, he does not seek compromise or try to draw a conclusion ambiguously like in the theory of Eastern Way-Western Means*.

Jang Jin’s style is classified as Eastern painting and this is not because of what he majored in college. Nor is it because of the materials he uses such as an ink-stick, crushed stone powders that are often used in the paintings of Far East. Moreover, it is not because of the fact that he made a modern version of spirit resonance or vitality, one of the key elements that define a painting in the Record of the Classification of Old Painter, a book written by Xie He, a writer and art historian in 5th century China. In fact, the way he sees and expresses the world challenges what the old philosophy of Eastern traditional painting presented as an ideal value and yet was never achieved, which makes him an Eastern painter. Jang explores the meaning of painting of this particular style in a most realistic way and at the same time maintains the philosophical depth of the concept.

A Path to Perception

At time, rational thought tend to despise emotion. Great sources of art subjects discovered through emotion are often undervalued and underused when an artist has a drift in his own thought and logics. For numerous contemporary artists, especially those who try to reconfigure the relationship between the world and objects based on rational thought, emotion is nothing more than a spice to the aesthetic recipe of an artwork. Yet, emotion is a pure and genuine element in Jang Jin’s works. The title of his individual exhibition held at Kumho Art Museum in 2009 was “Touching.” The artist encounters things and objects based on emotion, not based on rationality that tends to reorganize thoughts from the residue of senses.

However, it is impossible to explain the genesis of his works by the notion of emotion alone (here, emotion means similar to sensation). The author therefore employs the concept of anthroposophy that transcends the limitations of German Idealism of the 18th century; it is called, “understanding (verstand in German),” which developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant. Understanding is acquired through the development of native intelligence without the manipulation of rational thought, which is pure and direct (ding an sich in German, thing in itself in English). This in other words is enlightenment, which lies at the top of the perception structure composed of rationality, emotion and so forth. Against this backdrop, Jang Jin’s exhibition “Touching” gives an interpretation of the relationship between the artist and the object as well as between the artwork and the viewers on the horizon of understanding.

In the process of perception, which is based on understanding, Jang emphasizes the areas of senses and creates a figurative structure that can accommodate the senses of vision and touch. These senses come before taking the process of thinking – perception, memory and logical thinking – and the artist delivers such native senses to the viewers rather than intervening in the process in order to help them implement the process of their own accord. Of course there are other artists who create art from a perspective similar to Jang’s but what is special about him is that he tries to offer the viewers with as large shares to think as possible.

Landscapes Drawn with Energy

Jang Jin’s paintings bring up the image of landscapes as they reproduce landscapes that exist in his memory and life, which he aspires to express on the canvas. But the landscape he draws is not realistic as it is not drawn from nature. It does not have specific indications. The landscape as an object in his work is not sketched as an outline; the perspective has changed since the era of Paul Cezanne. Moreover, his Eastern painting style in a contemporary abstract quality is far from drawing a landscape of mental images. Created by using his body as the most essential and native medium of painting, his works are the product of painting in a highly abstract and yet realistic way. Decoding the very nature of landscapes conveyed through energy is at the core of his works.

Jang Jin picks an object to draw in a most direct way in the spaces he belongs to. Not just does he sketch it based on visual information he obtains, but he tries to feel it with his whole body. Perhaps that is why he tends to pay little attention to a figurative way of expressing it in a concrete and realistic fashion. As explained with the notion of understanding (verstand in German), the artist does not just observe the object with his eyes; he feels the sensation with his whole body that the landscape provides to him. Just like the lyrics of the song “Dancing in the Moonlight,” the sensitive artist dances with the landscape and becomes a sponge of emotion. He senses with his tentacles the subtle melody that the environment surrounding him plays out – and this later develops into his genres of landscape and history. At the studio, his tentacles (or his body) release an array of forms and shapes of energy into his works. In a way, his works of art resembles the works of abstract expressionists, such as Jackson Pollock; Pollock concentrates on the action of dripping paint onto a canvas to express his impulses liberated from unconsciousness. The artistic value, which is the traces of the action, largely depends on some sort of a ritual form of American Indians or the technique of automatism art after the Dada Movement. The root of the impromptu, spontaneous and direct attitude of abstract expressionism can be found in ancient Zen Buddhism. Pollock fascinated, by such a notion, created action painting of his own. A similar act of painting is employed by Jang Jin. Yet while Pollock connects his action with his impulses, Jang finds the sources of his action in energy from nature and his painting as an act is transzendental rather than impulsive.

From Landscape to History

His focus seems to have changed from the environment of the Mother Nature to a time frame; recently, Jang Jin has been drawing the history of Incheon, the city where he resides. Incheon, whenever dropping by, gives a particular impression to the author. Native-born Incheon citizens often say that “there is no such person as a native-born in Incheon.” A small fishing village called Jemulpo became the center of the Open-Port area in Incheon in the late 19th century. After that, Incheon was transformed into a modern city under the Japanese colonial rule and served as a historic site for the successful Incheon Landing Operation during the Korean War. Incheon is a city where past history remains in the buildings of the colonial period and today’s new development and strong demands for consumption exist simultaneously. And Jang Jin, who is originally from Incheon, is drawing the city’s history in his studio at the heart of the old part of the city. How he reads and interprets history is closely in line with how he sees landscapes; focusing on the outline of history, which only exists in the traces it has left. Instead of organizing history in an archive or index, the artist transforms his feelings about history into a form of energy on a canvas.

Jang Jin’s paintings are modern and contemporary; first of all, the emotions and the state of complete self-effacement expressed in those paintings do not at least fall into cheap sentimentalism, and second, his approach is to reveal the long-hidden emotional wounds of himself as well as the viewers of his works. Being contemporary in artworks means a creation of art through consistent synchronization with the past, which is explicitly expressed in Jang Jin’s works. The evidence of synchronization is easily found in his way of expressing history in the traces of energy, which exist in the form of painting, not in a text.

소·금·꽃

백 윤 수 I 철학박사

詩的空間 6 한지에 먹과 채색, 77x87cm, 2017

詩的空間 5 한지에 먹과 채색, 94x62cm, 2017

Moonlight prism 12(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 104cm, 2008

몇 년전 장진을 처음 보았을 때 나의 뇌리에 새겨진 것은 그의 조용하고 침착하며 아울러 자신의 목표를 향해 꾸준히 나아가는 성실한 자세이었다. 이번 그의 개인전에서, 처음 받았던 인상에 어긋나지 않게 수미일관해온 그의 삶과 예술의 행적을 다시 한번 확인할 수 있다. 동양회화에서 형사와 신사의 관계는 대상에 대한 묘사기교의 발전 및 현상세계에서 내재되어 있다고 여겨지는 도에 대한 추구와 결부되어 오랜 세월에 걸쳐 형성되었다. 그 과정에서 우리는 한비의 견마귀매론, 사혁의 화육법론, 일품화론, 문인화론, 개성주의 화론 등이 회화사적 면에서 중요한 역할을 담당하였음을 알고 있다. 이러한 역사의 궤적은 화가들에게 옛 전통의 가치를 존숭하는 태도를 길러준다. 사대부들에게 특히 많은 영향을 준 문인화론에는 여러 가지 특성이 있으나 회화의 주제와 동시에 필법과 묵법, 구도 등을 중시하며 용필에 있어서 서법을 중시하고 채색화 보다는 수묵화를 선호한다는 점에서 이전의 회화와 구별된다. 화가들은 그 이상을 실현하기 위해 동기창이 말하는 것처럼 만권의 책을 읽고 만리를 여행하여 그림에 문자향과 서권기가 우러나오게 노력하였다. 이러한 특성으로 말미암아, 문인화는 가슴 속에 이루어진 흉즁성죽의 이미지를 단숨에 그려냄으로써 외면적으로 천재성을 과시하는 것처럼 보일 수도 있으나, 내면적으로는 흉중성죽하기 위한 무한한 고뇌와 인내가 전제되어 있으며 이것이 창신이자 개성 발휘의 기틀임을 보여준다. 이러한 전통과 창신의 조화는 회화만이 아니라 문화의 모든 면에서 중심을 이루는 핵인데, 이번 전시회를 통해 확인 할 수 있는 것은 장진이 전통과 창신의 조화에 대하여 많이 생각하고 있다는 점이다. 그는 천여년이 넘게 이어져온 수묵화를 통해, 생태환경이라는 주제를, 새로운 용필과 용묵의 방법으로 우리에게 제시하고 있다.

주제의 선택과 또 그 주제를 화면에 전개하기 위한 구도, 용필, 용묵 등 묘사 방법에 대한 모든 것이 이미 가슴속에 완전하게 이루어진 뒤에야 비로소 화가는 망설임 없이 화선지에 붓을 그어 나갈 수가 있다. 그러기 위해 화가는 자연의 모습을 깊이 관찰하여 삼라만상이 지닌 각양각색의 형태와 선, 색채 , 움직임이 자아내는 미묘한 차이를 읽어내고 깊은 사색을 통해 그들에 간직된 독자적 의미와 가치를 발견하여, 화가의 예술관에 부합되는 이미지를 형성해 내어야 한다. 그리고 이에 그치는 것이 아니라 그러한 이미지를 구체적으로 화선지에 구현하는 방법과 기교를 구사하여야 한다. 동시에 매체로서의 종이, 붓, 먹, 다양한 색채 등등에 대한 자신의 생각을 구체화하는 과정에서, 과거로부터 내려오는 진부한 방법이 아닌 자신 의 독자적인 새로운 세계를 개시하는 창조적인 면을 제시하여야 한다. 이번 전시회에서 볼 수 있듯이 장진은 자신이 거주하고 있는 소래의 바닷가에서 매일처럼 보는 하늘, 바다, 갯벌, 언덕과 그 사이의 수많은 나무, 그루터기, 꽃, 풀, 바위, 흙과 더불어 생활하면서 그들과 대화를 나누고 그들이 내는 생명의 소리를 듣고자 노력하며, 동시에 자신이 받아들인 그들의 진실을 나름대로 표현하고자 하였다. 그에게 느껴진 생명의 소리가 구체적으로 어떤 것인지 우리는 모른다. 그러나 우리가 그의 그림을 통해 느낄 수 있는 것은 그가 진지하고 성실하게 그들과 대화하며, 새로운 방식을 통해 그 대화의 결과를 표현하려고 노력하며 또한 흔히 이야기되는 생태계의 고발이라든가 비관적인 미래의 제시라기 보다는 오히려 자연에 대해 따뜻한 애정을 지니고 있다는 점이다. 그 소리는 우리가 직접 들을 수 있는 것이 아니다. 우리의 마음이 그 대상에 침잠하여 그들과 우리 사이에서 맺어지는 상대적 가치부여의 관계를 벗어나 그 자체에 다가가야 한다. 그러기 위해서는 우선 대상이 지닌 외면적인 모습을 자세하게 관찰하여야 하며 동시에 대상의 본질을 발견해야 한다. 이것이 문인화가들이 말하는 신사이다. 이러한 신사는 결코 형사를 벗어나 완전한 추상으로 흐르지 않는다. 불가에서는 이를 공(空)의 개념으로 이해하고 있 다. 우리의 마음은 현상세계의 다양한 형태와 성질로 말미암아, 온갖 이해관계를 위시한 번뇌를 일으키므로 우리는 대상이 일시적인 것이고 영원한 것이 아니라는 생각을 할 필요가 있다. 그러나 대상은 결코 무가 아니다. 따라서 우리는 다시 현상 세계로 돌아오지 않으면 안된다. 이를 위해서는 십우도의 입전수수에서 암시하고 있는 것처럼 소와 내가 하나가 되고 그에 따라 일체의 삼라만상에 대하여 그 가치를 인정하고 사랑하는 감정이 이러나야 하는데, 우리는 장진이 주제를 취급하는 태도에서 이러한 애정을 읽을 수 있다.

장진에게 기대하면서 아울러 주문하고자 하는 것은 지금의 진실한 자세를 끝까지 유지해 달라는 것이다. 그러기 위해서는

광(廣)의 정신이 필요하다. 우리 주변에 산재해 있는 다양한 대상은 다양한 매체의 변화를 통해 표현될 수 있다. 장진은 장갑 낀 손가락을 사용하기도 하고, 폐인트 브러쉬를 구사하기도 하며, 먹의 다양한 농담과 더 나아가 빙묵이라는 새로운 기법을 계발하기도 한다. 이들은 단순한 시도가 아니라 오랜 세월을 통해 자기 나름대로의 새로운 방안의 제시, 실험, 실패,

반성, 동료와의 의논, 재시도 등을 거쳐 우리에게 제시된 것이다. 이러한 새로운 시도에 대하여 사회는 방어적 내지는 공격적 성향을 드러내기도 하는데, 화가는 이러한 경우 자신의 확고한 신념으로 자신의 태도를 견지하여야 한다. 석도가 당대의 정통 화단을 자처하고 있던 사왕에 대하여 개성주의를 주창할 때에도 역시 광의 정신으로 외로운 투쟁을 하지 않으면

안되었다. 우리가 익히 아는 바와 같이 『논어』에서는 사람을 품등하면서 광을 중행에 다음가는 것으로 삼고 있다. 적극적으로 자신의 이상을 실천하려 하지만 그 이상이 너무 높아 실천이 이를 따르지 못하는 경우가 광인데, 이 광의 정신은 양명학에서 오히려 가장 바람직한 성품이다. 이상을 이룩하는 과정에서, 그것이 실현되었을 대의 결과보다도 그 이상을 향하여

매진하는 열렬한 정신이 더 필요하기 때문이다. 그것은 처음부터 완성을 기대하지는 않는다. 부단한 시행착오를 겪더라도

굽히지 않고 초심을 버리지 않고 견지하며 다각도로 그 이상을 향해 나아가는 정신이 바로 광인 것이다. 장진에게서 보이는 시험정신은 분명 광의 일단을 보여주고 있다. 이러한 광의 정신은 대상이 발하는 생명의 소리를 듣고 그것을 자신의 내면에서 소화하여 다양하면서 새로운 방식으로 화면에 그려내며, 동시에 자신의 표현 의욕을 아무 허식도 없이 진솔하게 표현할 때에야 비로소 구현된다. 그것은 결코 쉬운 일이 아니다. 그러기에 우리 역시 새로운 세계를 개시하는 장진의 노력을

따뜻한 마음을 지니고 지켜보아야 할 것이다.

경계 위의 풍경, 풍경이 지워지고 드러나는 계기

고 충 환 I 미술평론

Moonlight prism111(시적공간) 한지에 먹과 채색, 50x50cm, 2016

Moonlight prism111(시적공간) 한지에 먹과 채색, 50x50cm, 2016

詩的空間 6 한지에 먹과 채색, 77x87cm, 2017

詩的空間 5 한지에 먹과 채색, 94x62cm, 2017

Moonlight prism 12(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 104cm, 2008

풍경을 오래 바라보고 있으면 순간적으로 세부가 지워지면서 단순해질 때가 있다. 빛 속에서는 결코 자기를 드러내지 않는 이 단순한 풍경은 태생적으로 어둠과 더 친숙하며, 어둠 속에서 비로소 자기의 속살을 보여준다. 모든 풍경은 이처럼 그 속살을 자기 내부에 숨기고 있다. 특히 낮과 밤, 빛과 어둠이 극명하게 갈리는 자연 속에선 더욱 그러하다. 온갖 현란한 불빛들이 명멸하는 도시에서의 풍경은 결코 단순해지지가 않는다. 도시에서의 사물은 자기의 존재가 지워지기라도 할 것처럼, 망각 속으로 사라지기라도 할 것처럼 기를 쓰고 어둠을 밀어낸다. 이에 반해 자연은 어둠을 포용한다. 자연 속에서 사물은 낮동안만 자기를 드러내 보일 뿐 밤과 더불어 자기를 지운다. 그리고 거대한 실루엣을 되돌려준다. 칠흑같은 어둠 속에서의 풍경은 사물과 사물간의 경계가 지워진 마치 거대한 유기체 덩어리와도 같은 실루엣으로 드러난다.

장진의 그림 속의 풍경은 이처럼 단순하다. 엄밀하게 말해, 처음부터 단순한 것이 아니라 작가에 의해 비로소 단순해진, 단순화된 풍경이다. 풍경이 그 속에 단순한 계기를 숨기고 있고, 작가가 이를 불러낸 것이다. 풍경의 본질 혹은 원형으로 부를만한 그 계기는 그저, 저절로 주어지는 것이 아니다. 풍경과 작가를 가로막고 있던 경계가 허물어질 만큼의 충분한 동화 이후에나 비로소 풍경은 스스로를 열어 보인다(이를 하이데거는 세계의 개시라고 부른다). 이때의 풍경은 작가와의 동화 의 소산인 만큼 풍경 자체의 자족적인 것인 동시에 작가에게 속한 것이기도 하다. 그러니까 작가가 풍경 속에 투사한 자기 즉 작가의 분신인 셈이다. 이를 육화된 풍경, 체화된 풍경으로 부를 수 있을 것이다. 작가는 이처럼 육화되고 체화된 의식의 형태로서 풍경과 연속돼 있으며(이를 메를로 퐁티는 우주적 살이라고 부른다), 이미 그 자신 풍경의 일부인 것이다. 이는 풍경을 사물화하고, 객체화하고, 대상화하는 프로세스를 통해서는 결코 거머쥘 수 가 없다. 그러니까 작가와 풍경을 주(主)와 객(客)으로 분리하고, 작가 자신으로부터 풍경을 멀찌감치 떼어놓는 식의 분석의 소산이 아닌 것이다. 오히려 작가의 그림은 풍경에의 동화와 해석(그 속에 일정부분 동화의 계기를 포함하고 있는)의 소산이다.

이렇듯 장진의 그림은 분석의 결과물이 아니므로 그림 속에서 사물의 실체를 확인해보려는 노력은 실패할 수밖에 없다. 말하자면 '이 그림은 강화를 배경으로 그려진 것이다'라는 표면적 사실을 이 그림은 배반한다. 강화도에 대한 지정학적 사실, 감각적 사실을 그린 것이 아니기 때문이다. 그렇다면 이 그림과 강화와의 의미관계는 어떻게 찾아질 수 있을까. 강화를 배경으로 했거나 소재로 했다는 그 표면적인 사실의 진정한 의미는 무엇일까. 결론적으로 작가의 그림은 강화의 지정학적이고 감각적인 사실 저편의 한 지점을 겨냥하고 있다. 풍경의 표면(감각적 사실로서의 현상)과 이면(관념적 사실로서의 본질)의 경계를 허물고 강화가 그 전체를 드러내 보이는 한 지점을 겨냥하고 있는 것이다.

이는 일종의 암시적인 풍경 곧 그 속에 잠정적인 움직임을 암시하는 풍경으로 나타난다. 물론 그 움직임이란 자연의 변화무쌍한 성질로부터 온 것이다. 변화하는 것을 고정된 형태로 붙잡아 들이는 유일한 방법은 암시적인 것이다. 우듬지를 흔드는 바람과 그 바람에 묻어온 대기의 알갱이 그리고 손끝에 감촉되는 습윤한 기운과 같은 온갖 변화하고 움직이는 자연의 계기들이 그림 속에 거둬져 있는 것이다. 작가의 단순한 그림은 이처럼 생략된 그림이 아니라 함축된 그림이다. 마치 주름처럼 움직임의 계기들이 겹쳐져 있고, 마치 지층처럼 변화의 계기들이 포개져 있는 것이다. 그 레이어들 한 겹 한 겹이 그 대로 강화의 바람과 공기를, 강화의 시간과 공간을 함축하고 있는 것이다.

강화가 그 전체를 드러내는 풍경의 한 지점이나 그 속성은 어떻게 찾아질 수 있을까. 장진의 근작은 이러한 물음에 바쳐져 있다. 작가는 그 해답을 강화의 암시적인 자연에서 찾으며, 특히 바다를 배경으로 한 섬이라는 강화의 장소특정성에서 찾는다. 그리고 이는 바다와 하늘이 접해있는 수평선과 산과 하늘이 면해있는 지평선(혹은 공지선), 그리고 바다 한가운데 드문드문 떠있는 섬들로서 드러난다. 그러나 작가의 그림에서 이처럼 다른 풍경의 지점들이나 그 계기들을 구분하는 것은 무의미하다. 강화의 자연을 그릴 때처럼 이는 암시적인 풍경 속에 해체되고, 그 구분과 경계를 허물고 있기 때문이다.

이처럼 수평선과 지평선을 배경으로 한 풍경은 자연스레 옆으로 긴 그림으로 나타나는데, 그 세부를 무시하고 본다면 이는 마치 미니멀리즘 회화의 추상화면을 보는 것도 같다(미니멀리즘 회화가 회화의 본질에 천착한 배제와 배타의 논리적 산물 이라면, 작가에게서의 단순한 화면은 모든 계기들을 그 속에 끌어안고 녹여낸 함축과 암시의 소산이다). 또한 옆으로 긴 그 림은 세로로 서 있는 그림에 비해 작가와 풍경이 하나로 연장되고 연속된 듯한 느낌을 강화해준다. 그렇게 바다와 하늘, 산과 하늘이 접해있는 선(線)은 동시에 작가와 풍경이 서로 만나고 동화되는 지점이기도 하다. 그 선은 아득하고 멀고 심리적 이다(이는 작가와 풍경이 심정적으로 서로 동화돼 있음을 증명해준다). 그 지점은 비록 작가의 감각에 붙잡힌 것이긴 하지만, 정작 그로부터 느껴지는 인상은 감각을 벗어난 비현실적인 비전을 향해 열려 있다.

작가가 근작에 부친 '시적 장소'라는 명제는 아마도 이런 의미, 즉 감각의 소산이지만 정작 감각을 벗어나 있는 풍경, 현실에 속해 있지만 정작 현실을 넘어선 풍경이라는 의미로 이해할 수 있을 것이다. 작가가 자기에게 감각적으로 어필돼 오는 풍경의 휘장을 찢고, 그 뒤쪽으로부터 끄집어내고 캐낸 (원형적) 풍경, 다시 말해 (감각적) 풍경이 자기 속에 품고 있던 내적 계기들을 작가에게 내어주고 열어 보인 (원형적) 풍경, 작가와 하나로 삼투되는 풍경으로 이해할 수 있을 것이다.

그 풍경은 감각의 한계를 넘어서는 숭고한 감정을 불러일으키고, 인간의 인식이 미치지 못하는 생명의 비밀을 드러내 보인다. 그 풍경의 선은 실제로는 없는 것이며, 단지 인간의 감각과 인식이 그어놓은 금에 지나지 않는다(그 선 자체는 인간의 한계를 증명한다). 작가는 아마도 이처럼 있는 것과 없는 것이 서로 맞닿아 있는 지점, 존재하는 것과 부재하는(다만 암시 될 뿐인) 것이 그 경계를 허무는 장소로서의 강화를 그린 것이리라.

이렇게 그려진 강화는 온통 붉다. 노을과 갯벌에 피어있는 키 작은 소금꽃 군락이 강화를 온통 붉게 물들이고 있는 것이다. 노을 자체는 빛에 속한 것이지만, 정작 그 실체가 더 잘 드러나는 때는 사물들이 자기의 실체를 지우기 시작하는 어둠과 대비될 때이다. 그리고 소금꽃(바다 속에 핀 꽃)은 생명의 비의(삶과 죽음, 에로스와 타나토스가 맞물려 있는)를 드러내고, 생명에의 경외감을 자아낸다. 이처럼 붉게 물든 노을과 소금꽃 자체는 그대로 작가 자신의 마음의 밭이기도 하다. 이렇게 장진의 화면(마음) 속에서의 강화는 어둡고 단순하게, 그리고 붉게 자신을 드러내 보인다.

A Landscape on a boundary, moment of blurring and revealing of landscape

Kho, Chung-Hwan I Art critic

Moonlight prism111(시적공간) 한지에 먹과 채색, 50x50cm, 2016

Moonlight prism111(시적공간) 한지에 먹과 채색, 50x50cm, 2016

詩的空間 6 한지에 먹과 채색, 77x87cm, 2017

詩的空間 5 한지에 먹과 채색, 94x62cm, 2017

Moonlight prism 12(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 104cm, 2008

A landscape becomes simple momentarily when it is watched for a long time. The simple landscape which never reveals itself in the light is innately familiar with darkness and only shows its real features in the darkness. Likewise, all landscapes hide their true appearances in themselves. In the nature where day and night, and light and darkness are distinctively separated, this phenomenon is remarkably stuck out. A city where various dizzy lights are flickering never allows a landscape to become simple. In a city, things strenuously struggle with darkness as if they are removed or vanished into oblivion. On the other hand, nature embraces darkness. In the nature, things reveal themselves only during the day time and disappear when night falls returning their huge silhouettes. A landscape looks like a large organic body which boundaries between things are blurred in the darkness.

The landscapes of Jang Jin’s paintings are simple. However, they are deliberately simplified by the artist. The landscapes hide simple moment inside of it and the artist brought it out. The moment which is called the essence or prototype of landscapes is not created of itself. The landscapes don’t open themselves until assimilation that tears down the barrier between a landscape and an artist makes progress fully. (Heidegger referred to this as ‘disclosedness of world’). That moment, as the landscapes came into being out of assimilation with the artist, they belong to him as well as support themselves so that they can be called embodied landscapes or an alter ego of the artist.

An artist is linked with a landscape as an embodied or substantiated consciousness (Merleau-ponty referred to this as ‘cosmic body’)and he or she already turned into as a part of the landscapes. This cannot be made through the materialization, or objectification of the landscapes. In other words, it never happens if one tries to separate the artist from the landscapes as if to separate them as principal and auxiliary. Rather, it is the result of assimilation and interpretation of the landscapes.

As Jang’s paintings are not the results of analysis, it is useless to identify the real figure of things. ‘This picture is made with a scene of Kanghwa’ betrays the painting because it does not depict the geopolitical and sensible fact of Kanghwa. Then how is the relationship between this painting and Kanghwa figured out? What is the true meaning of the fact that this picture chose Kanghwa as a subject or is drawn with the scene of it?

Jang’s picture is aiming at a point beyond the geopolitical and sensible point of Kanghwa. It points at a spot that demolishes the boundary between the surface of landscape(phenomenon as a sensible fact) and the other side(substance as a idealogical fact) revealing whole Kanghwa. Jang’s picture displays the landscape which implies provisional movements. The movement originated from variable characters from nature. The only way to capture variable things to fixed shape is hinting something. All natural moment that varies and moves such as wind shaking a treetop, air that carried by the wind and damp feeling on a fingertip are reflected in the picture. Jang’s simple picture is an implicative one not an omitted one. Just like creases, the moment of movement are overlapped and so are the moment of change like layers. Each fold of the layers comprises the wind, air, time and space of Kanghwa.

How a spot in Jang’s landscape that displays the whole scene of Kanghwa or the properties of Kanghwa can be found? Jang’s recent works adhere to that point. He tries to find the answer from suggestive nature of Kanghwa and its geographical characters as an island. A horizontal line where the sea and the sky meet, another line that mountains and the sky encounter and sparsely floating small islets on the sea are indicators of the characters. However, it is meaningless to distinguish all the different spots or moment in the Jang’s painting because they are integrated in the suggestive scenes blurring boundaries.

Jang drew pictures with horizons long in width. Putting aside the detailed parts, it looks like an abstract painting of minimalism. (Minimalism can be taken as a logical result of elimination and exclusion digging into the essence of painting. On the contrary, Jang’s simple picture is the outcome of implication and suggestion. It comprises all moment and melts it.) Compared to a picture long in length, long picture in width strengthens the feeling of extension and continuance. All lines and horizons in the picture are places where an artist and the landscape meet and assimilation between them happens. Those lines are far and remote. (It proves that the artist and the landscape are emotionally empathized each other.) The spots, even though, were captured by the artist, impression from them is open for unrealistic vision beyond the sense.

Jang put a title of his recent works as ‘poetic space’. It can be understood that all this works are the results of sense but he described landscapes over the sense. They belong to reality but again the landscapes go beyond it. The artist ripped off outer screen of the landscapes of sense and dug a prototypical one from it. In other words, the landscape of sense gave its inner moment to the artist and he opened it. There, the landscape and the artist melted together and become one.

The landscapes go over the limit of sense, bring up sublime emotions and reveal secrets of life that men cannot reach. The lines in the landscape actually does not exist but only is drawn by the sense and cognition 17 · luis of men (The lines themselves prove that limit of men) The artist drew a spot that existence and non-existence encounter.

For Jang Jin, Kangwha is a place that existence and non-existence encounter each other and tears down the boundaries and he tries to portray the scene. In Jang’s paintings, Kangwha is all red. The colonies of salt flowers that blossom in the foreshore at the evening glow dye Kangwha all red. Evening glow itself belongs to light but the entity is clearly revealed when things are about to erase themselves. In the picture, salt flowers(blossomed flower in the sea) indicate the pathos of life that life and death, and Eros and Thanatos are embedded.) and evoke awe of life. The red glow and salt flower are artist’s field of heart. In his mind, Kangwha shows itself simple and red in the darkness

장진의 감각(感覺)을 의심하는 창조적 감각, 또는

‘계속적으로 새로워지는 즉시성(卽時性)’

심 상 용 I 미술사학 박사, 동덕여대교수

Sympath with my heart 한지에 수묵, 160x130cm, 2009

詩的空間 6 한지에 먹과 채색, 77x87cm, 2017

詩的空間 5 한지에 먹과 채색, 94x62cm, 2017

Moonlight prism 12(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 104cm, 2008

장진의 이미지는 감각적이다. 세련된 절제미, 담백한 먹의 실현, 자연의 사색, 먹과 주사먹의 강렬한 대립, 특히 주사먹의 농담이 만들었던 불타는 듯 노을의 이미지… 그 저변에는 먹에 대한 얄팍하지 않은 이해가 있다. 이는 작가의 오랜 치열한 실험과 모색, 시행착오와 반성의 대가로 주어진 것이다. 그 결과, 장진의 먹색은 스스로를 평정을 위태롭게 하고, 안정을 뒤흔드는 실험들 속에서도 품위를 잃지 않는다.

장진의 회화는 더 깊고 심오하며, 본질에 다가서는 지각을 추구해 왔다. 그가 무수하게 갯벌을 그리고 갈대를 스케치할 때도, 그는 그 단순한 외관을 재현하는 것에서 그치지 않았다. 묘사와 서술은 그가 걸어왔던 여정이 아니다. 장진의 것은 오히려 세계와의 접촉지점을 줄여나가는 과정으로 이해될 수 있다. 예컨대, 감각의 자극하고 흥분시키는 요인들을 배재하는 것, 화려한 문제나 공허한 위트, 수려한 기술적 조치, 변화무쌍한 기예의 절제, 완화, 소거. 장진이 마주하기를 고대하는 본질은 과학적인 그것이 아니다. 일테면 인간이 염분과 당, 철과 수분으로 이루어졌다는 식의 담론과는 하등 무관하다. 사회적인 것도, 초월적인 것도 아니다. 그것은 소음, 동요, 혼돈의 요인들로부터 벗어나 세계 그 자체 앞에 서고자 하는 지향성 같은 것이다.

장진의 회화는 자연으로부터 출발하지만, 자연의 외적인 재현을 넘어 나간다. 외모는 때로 너무 번접스럽다. 그것은 관조된, 또는 관상(contemplation)된 자연이다. 그것에 의해 자연의 본성은 가장 잘 스스로를 드러낸다. 그것은 ‘작가와 풍경이 하나로 삼투되는’ 풍경이다.(고충환) 임의적인 해석의 칼날을 들이대는, 즉 사물을 주체성으로 강간하는 것과 거리가 먼, 작가 자신의 표현을 빌자면 ‘시적 공간’을 허용하는 방식이다. ‘시적(poetic)’의 의미에는 현실과의 긴장관계가 암시되어 있다. 현실과 무관하지 않지만, 현실에 예속되거나 귀속되지 않는 질서의 의미인 것이다.

시적 토양은 장진의 미학적 노선을 대변하는 개념이다. 이번에 그는 자신의 토양을 더 깊이 경험하고 경작하는 쪽으로 나아온다. 시어(詩語)의 내밀한 차원으로의 더 깊은 침잠을 허용하는 방향! 해서 그의 근작들은 사물의 세계와 기억으로부터 더 멀어진다. 선(線)은 사물의 재현에 더 이상 연연해하지 않는다. 붓은 화폭 위에서 더욱 온전한 자유를 추구한다. 오로지 자유로이 자신의 단속과 연속, 강약과 장단에 집중한다. 규범, 세련미, 관습이 지정하는 조화, 타성에 젖은 균제미 등은 더 이상 의미있는 기준이 아니다. 그 자체가 목적은 아니지만, 풍경은 조용히 자취를 감춘다. ‘서술(narrative)’이라는 유형의 질서도 차지할 자리가 없기는 매한가지다. 빈자리는 ‘시’라는 이름의 의심, 질문, 저항, 실험과 같은 자유의 담화들의 몫이다. 여기서 예술은 ‘거울’이 아니라, ‘베일’에 가깝다.

그렇더라도, 이 시적 저항과 자유를 세계와의 결별이나 단절로 독해할 필요는 없다. 그것은 다만 세계의 지각된, 낯익은 인상이 아닐 뿐이다. 하지만, 세계가 위태로운 불명료함 속에서 더욱 선명하게 자신을 드러내는 경향이 있음을 생각할 때, 그 불편한 개방성이 오히려 더 궁극적으로 세계를 포착하는 방식일 수 있다. 우리의 지각체계에 즉각 부합하지 않는 이 모호함의 이미지는 뭔가 새로운 세계로 이어질 여지를 머금고 있는 잠시의 중단, 새로운 사고와 행동으로 이어지기 직전의 창조적 정지의 순간이기도 하다. 세계와 사물이 더 투명하게 드러나기 직전의 에너지로 가득한 불안정한 어두움, 창조적인 부재 …, 퀘이커 교도인 토마스 켈리(Tomas Kelly)의 표현이 여기에 적절하다. ‘계속적으로 새로워지는 즉시성’! 긴장을 머금은 한 순간의 존엄성, 그것은 종료가 아니라 과정이며, 사건 이후가 아니라 그 한 가운데다. 이는 장진이 자신의 회화를 결론을 향해 치닫는 괴물이 되지 않도록 주의를 기울인 결과일 것이다. 이야말로 결론을 생각할 즈음, 다시 개방으로 나 아가는 그의 태도의 산물인 것이다.

장진의 세계는 폭 보다는 깊이를, 도시적 세련미보다는 진지함을 추구하는 쪽으로 나아간다. 어떤 면에서 그의 먹의 실현은 이전보다 덜 자극적이고 더 실험적이다. 그 색은 더 이상 기름진 세련미를 표방하지 않는다. 기예와 기술은 억제되어 있다. 서술의 욕구를 더욱 줄인 결과, 세계로부터 조금 더 초연해지고, 멀어졌다. 장진은 자신의 회화가 여전히 실험과 연관된 것이기를 바란다. 그것이 몸에 밴 감각과 사고활동의 안주를 다시 역동시키는 데 유효하기 때문이다. 장진에게 그것은 매너리즘, 곧 의식과 그 실현 전체가 자동항해를 하는 비극적인 결과에 도달하지 않기 위한 기제다.

장진은 감각이 없는 작가가 아니다. 하지만, 감각은 남용되어선 안 될 도구라는 사실을 그는 알고 있다. 그것은 정신의 긴장감을 흩트리고, 피상에 머물게 하며 어떤 ‘본질적인 불확실함’을 지각하지 못하도록 하는 경향이 있기 때문이다. 그리고 무엇보다 감각은 ‘보다 순수한 감각’으로 나아가기 위해 요구되는 필연적인 집중과 성찰을 방해하기 때문이다.

장진의 회화는 성능이 좋은 감각의 결과라기보다는 그것과의 싸움의 결과에 더 가깝다. 여기에서는 감각과 그것을 진정한 의미로 상승시키는 감각에 대한 의구심이, 재능과 그것을 통제하는 의식적 실험이 동시에 목격된다. 장진이 창작자로서 좋은 자질을 겸비하고 있다는 반증이 아닐 수 없다.

A creative sense suspecting senses

or

'continuously renewed instantaneousness'

Shim Sang Yong I Ph.D in Art History, professor at Dongduk Women's university

Sympath with my heart 한지에 수묵, 160x130cm, 2009

詩的空間 6 한지에 먹과 채색, 77x87cm, 2017

詩的空間 5 한지에 먹과 채색, 94x62cm, 2017

Moonlight prism 12(詩的空間) 한지에 먹과 채색, diameter 104cm, 2008

Jang Jin's images are sensuous. They include beauty of sophisticated temperance, realization of plain and

simple indian ink, deep contemplation of nature, striking contrast between indian ink and cinnabar ink and particularly, blazing image of dusk by the degree of strong and faint of cinnabar ink. That is, Jang has deep

understanding of indian ink and it is a result obtained by through and repeated experiments, search and trial

and error. His intense efforts were paid off because his ink colors in the pictures got a certain level of

elegance and grace even in the middle of various experiments that make serenity rocky and sway stability.

Jang's painting has been in pursuit of perception which is deep and steps closer to essence. Myriads of

sketches for the foreshore and reeds by Jang have always been more than realization of external appearance.

Description and depiction were not a passage that he had walked down. Rather, Jang‘s paintings should be

understood as a process that reduces contact point with a world. His purposes are to exclude factors which

stimulate senses, to temperate splendid matters or empty wits to mitigate extravagant techniques and to

remove kaleidoscopic craft. The essence that Jang wants to encounter is not scientific. Neither they are

related to a discourse that humans beings are composed of salt, sugar, iron and water nor sociable or

transcendental. It is rather directivity that aspires to stand before a world by being free from noise,

disturbance and chaos.

Jang's painting starts from nature but it goes over realization of its outer cover. Being contemplated and mediated, outer space is too complicated. The true character of nature is represented the most by contemplation. That is so called, 'The landscape and the artist melted together and become one.'(quoted from an introduction of Jang's former solo exhibition 'Poetic Space' written by Koh Chung-Hwan) It is very different from brandishing the blade of arbitrary interpretation or assaulting objects subjectively. Rather, it allows to have 'poetic space' which is borrowed from artist's own expression. Again, it means order that is not subject to reality linking with it at the same time.

Poetic soil refers to a concept of Jang's aesthetic line. His painting is moving forward to experience and cultivate the soil deeply. It delves into even a deeper and clandestine sphere of poetic words. Therefore, Jang's recent works are drifted farther and farther from the world of objects and memories. Lines are not ardently attached to realization of objects. Brush-strokes seek for sound freedom only focusing on his own intermittence and continuity, strength and weakness freely. Harmony determined by rules, beauty of polish and tradition and symmetric beauty created by force of habit are not meaningful standard any more. Even if it is not a purpose in itself, landscape disappears quietly. Order named 'narrative' does not have a spot to stand either. Empty space now is prepared for free discourse such as doubt named 'poem', questions, resistance or experiments. Here, art is closer to a 'veil' not a 'mirror'.

However, one does not need to translate this poetic resistance and freedom as separation or alienation from the world. They are not just familar impression recognized by the world. Considering that the world has a tendency to reveal itself distinctively in the risky obscurity, the uneasy openness may be a way of capturing the world ultimately. The vague images which do not correspond to our system of perception are a state of pause which is possible to link with a new world and a creative standstill that right before entering into new thought and action. In other words, they are unstable darkness and creative absence that filled with energy which is on the verge of transparent revelation of world and objects.

What Tomas Kelly who was a Quaker said, 'continuously renewed instantaneousness' is quite relevant here. Dignity of a moment that comprises tension is not an end but a process and refers to presently ongoing incident not a situation after the incident. All these stem from Jang's efforts that prevent his paintings from changing to a monster that rushes up to a conclusion. In a nutshell, it is a fruit of Jang's attitude towards openness.

Jang's world is making headway toward profoundness and seriousness rather than width and urban sophistication. In some respect, his presentation of indian ink is less stimulative and experimental, colors are not richly refined. And technique and craft are suppressed. As he had reduced the desire of description, paintings are farther from the world and became a little more aloof. Jang still wants his paintings are linked with an experiment because that is effective for reactivating stagnated thinking and habituated senses. To Jang, it is a mechanism that checks a tragic result that leads his consciousness and entire realization to sail automatically.

Jang Jin has good senses of art but he knows that senses are not methods to use improperly because they

may let tension of minds go loose and remain on superficial level and prevent minds from perceiving 'intrinsic

uncertainty'. Above all, Senses obstruct imperative concentration and introspection which are required to

develop 'purer senses'. Jang' paintings are like the legacy of the struggle rather than a result of good senses.

In his paintings, senses and doubts that elevate the senses into true meaning and talents and conscious

experiments that control the talents are found at the same time. And that is evidence that Jang Jin has a

superb quality of becoming a creator.